We just marked the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, and as I sat writing this column at home, I could gaze out the window at a day that would have made its founders proud. Washington, D.C. is currently enjoying its cleanest air in at least 25 years, thanks to decades of local, state, and federal policies combined with a wet, windy spring. Bicycles abound; there’s almost no car traffic. Birdsong awakens us, sometimes far too early. There is, of course, a global pandemic element to the quietness, and pandemic-induced shutdowns are really not the way to way to get clean air. The same way an economic collapse is really not the best way to get cheap gasoline.

There’s another thing I can see that Earth Day’s founders would be delighted by. On my roof, barely visible through a skylight, is a solar-power system that will more than meet my power demand for the day. It’s a small thing now, but it would have been an unimaginably big deal in 1970. Five decades on from the first Earth Day, an energy revolution that started low and slow is now changing the world in real time.

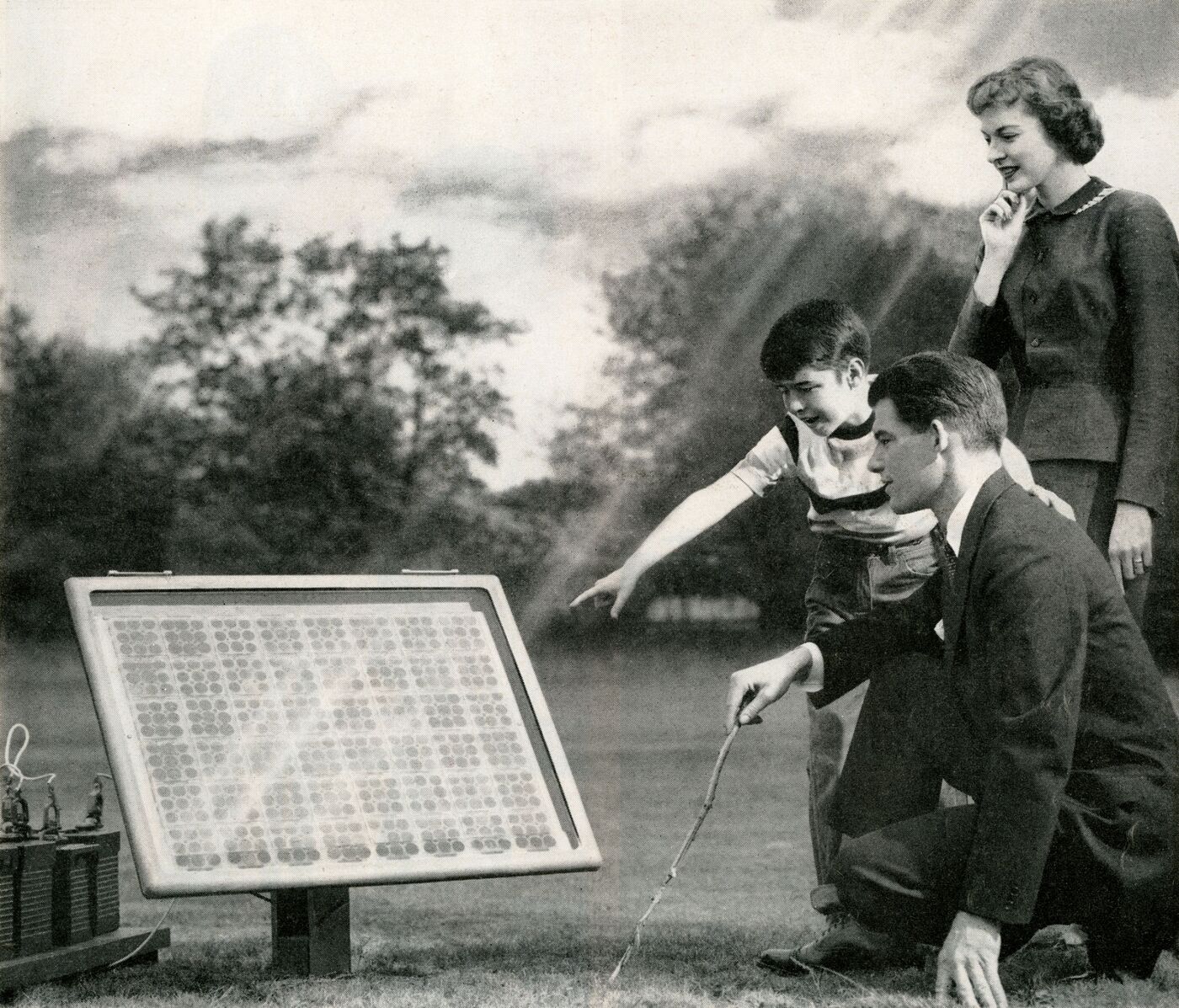

It all started 16 years before the first Earth Day, in 1954, when Bell Laboratories unveiled the first photovoltaic cell. They called it the “solar battery,” and the ads for it are charming. “The same kindly rays that help the flowers and the grains and the fruits to grow,” reads one, “also send us almost limitless power.” But the early marketing also contained a strong dose of realism: “There’s still much to be done before the battery’s possibilities in telephony and for other uses are fully developed.”

Much to be done, indeed. Photovoltaics were wildly expensive, complex to produce, and tiny. There wasn’t even a commercial application for them until 1962 with the Telstar 1, the “first privately sponsored space-faring mission” and the first satellite to relay a transatlantic television signal. Now solar power is standard on satellites.