It will go down as wildest of the shale wildcatters, the overreaching pioneer of fracking techniques that minted vast fortunes and, now, have left behind ruin. At long last, financial reality has caught up with Chesapeake Energy Corp., avatar of the boom and subsequent bust of North American shale.

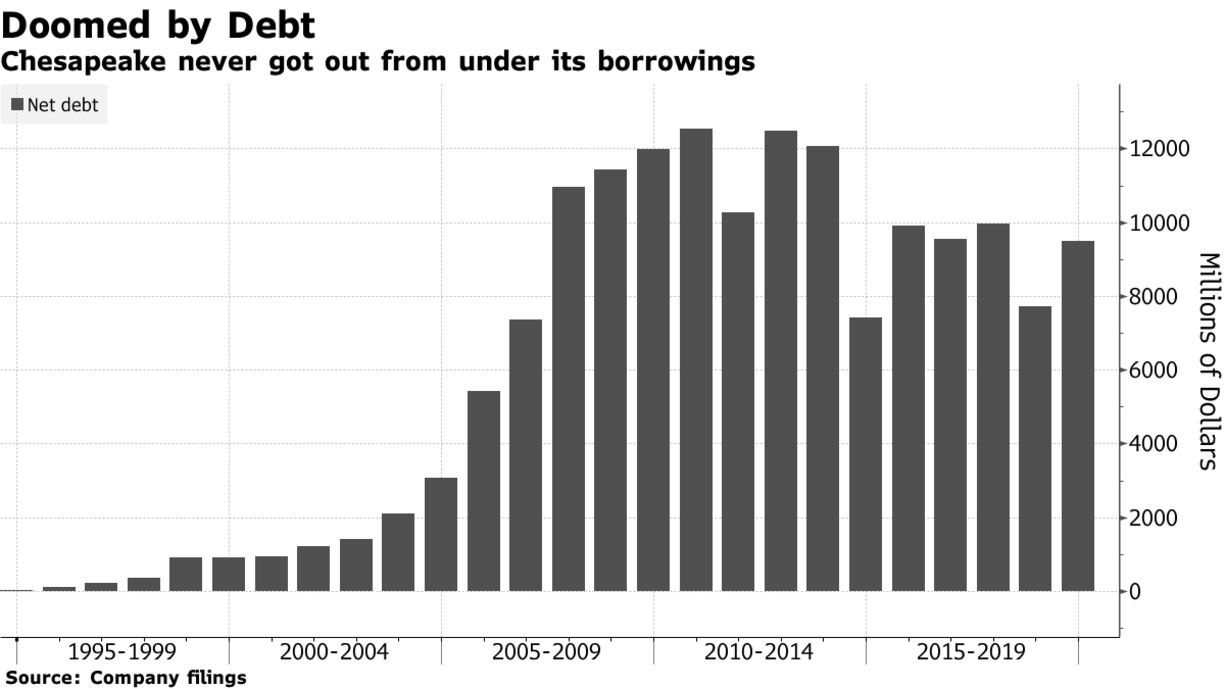

Chesapeake’s spiral toward oblivion accelerated this week with executives said to be preparing for a potential bankruptcy filing, signaling the imminent end of Chief Executive Officer Doug Lawler’s 7-year campaign to turn around the troubled gas explorer. For a company that’s been skirting disaster for most of the past decade, the Covid-19-driven collapse in world energy prices merely added one more exclamation point to a tale of risk, hubris and debt.

Chesapeake may be shale’s biggest corporate casualty, but it is hardly the first — and won’t be the last. Its self-inflicted wounds have sapped confidence across the entire industry, leaving many smaller operators teetering on the edge of catastrophe.

As the remnants of shale’s turn-of-the-century heyday turn to dust, it’s unclear who — if anyone — will step into the void. Supermajors like Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. already have written off their own gas-heavy assets, and are instead focusing on oil-rich shale fields. But any shift in the global supply-and-demand balance for gas would prompt the most sophisticated giants to reassess the value of acquiring and drilling mothballed gas projects.