China has used offers of generous subsidies to amass the world’s largest array of wind and solar power. But there’s a problem: it’s not fully paying them. Renewable energy projects have grown far faster in recent years than the pool of money the government sets aside to pay the fees it promised them. The result is a total debt of $42 billion and growing, according to one analyst, with a payoff not seen until 2041 without a change in policy.

Subsidy Burden

China’s subsidy deficit could be fully paid down by 2041 after a peak in 2032

Source: BOCI Research Ltd.’s estimates

While China is moving away from subsidies for new projects, the delayed payments are weighing on developers and restricting their ability to borrow more money to fund new generation. The issue is of particular importance because of the huge amounts of money pouring into the sector in China — $818 billion in the last decade, more than double any other country, according to BloombergNEF.

“Without structural change to address the issue, the subsidy receivables in the whole industry would continue to grow and drag companies’ balance sheets and investment capabilities,” Tony Fei, an analyst with BOCI Research Ltd., said in a July 6 note.

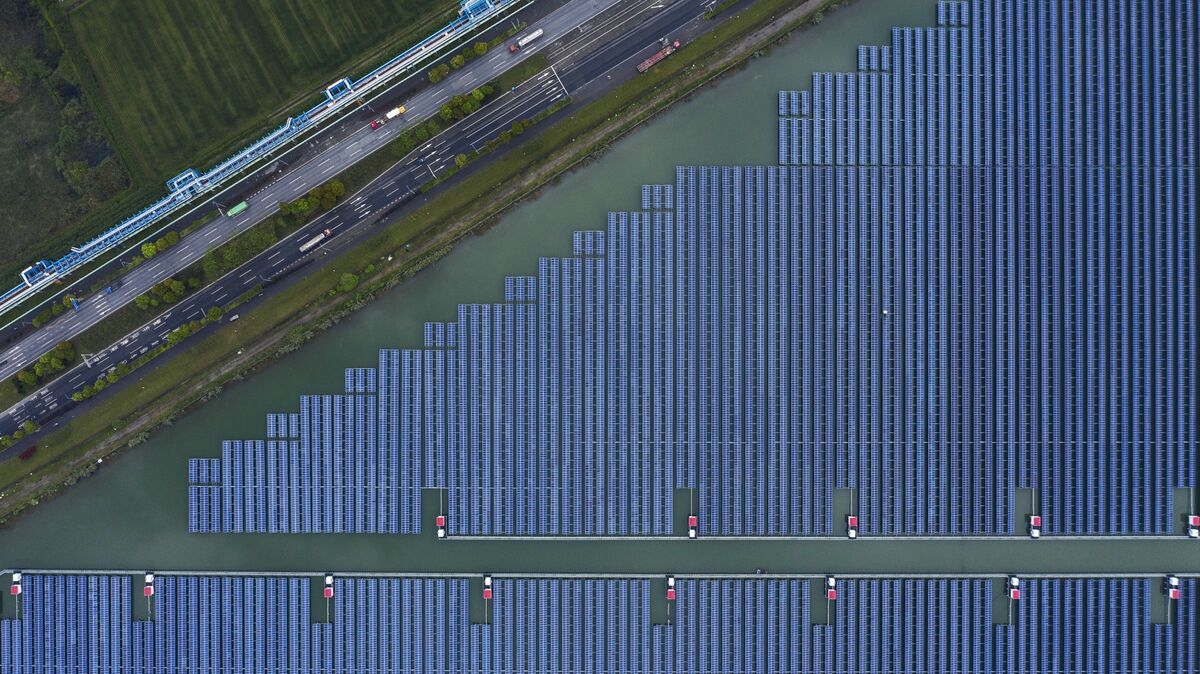

Photovoltaic panels in a floating solar farm on the outskirts of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

China for several years now hasn’t been paying its full subsidy bill, and the mountain of debt keeps growing higher. The government funds the payments with a surcharge on electricity bills, and hasn’t been willing to increase that or find new sources as the number of subsidy-eligible wind and solar projects soared last decade.

Longyuan now trades below its book value because of the mounting delayed payments, said Robin Xiao, an analyst at CMB International Securities Ltd. Denmark’s Orsted A/S, another energy company with a large portfolio of wind assets, trades at nearly 5 times its book value, by comparison.

The low valuation for Longyuan and other the Chinese renewable firms restricts them from issuing more equity to fund new projects, Xiao said. That’s leading to a rash of privatizations on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Other private developers, such as GCL New Energy Holdings Ltd., have had resort to selling off their renewable power assets to help reduce debt. Chinese state-owned developers, which have easier access to low-cost capital, are happy to snap up such projects, BloombergNEF analyst Jonathan Luan said.