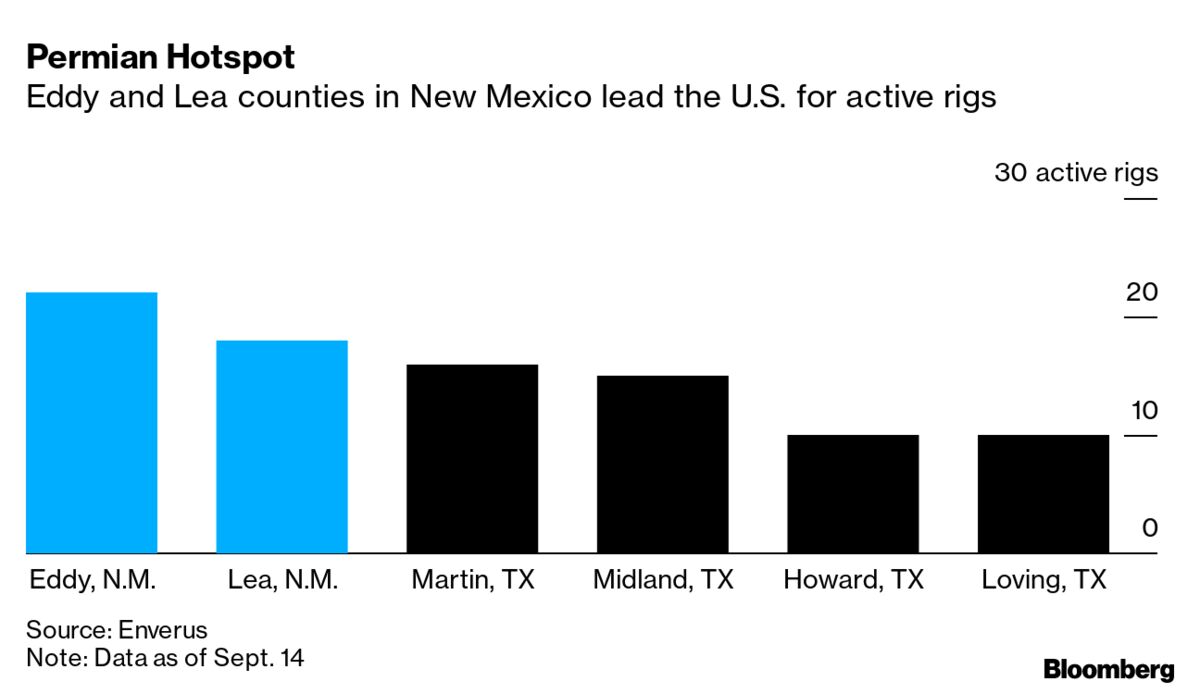

With the U.S. oil industry reeling from the collapse in demand this year, the New Mexico shale patch has emerged as the go-to spot for drillers desperate to squeeze as much crude from the ground without bleeding cash. There’s just one problem: Joe Biden wants to ban new fracking there. Just over the border with Texas, in a two-county stretch that forms the far western edge of the Permian shale basin, there are more rigs boring oil wells today than anywhere else in the nation. The rock here, once overlooked by wildcatters obsessed with the much-bigger Texas side, has quietly become the most profitable place to produce oil in America. That’s attracting cash-strapped fracking outfits after the pandemic pushed crude prices down to just $40 a barrel.

“This is the main place right now pretty much,” said Clyde Cox, a 27-year-old who has been hauling equipment to frack locations in the state for the past six months. Back in the summer, he was only servicing one frack site in the area. Today, he’s up to three. If Biden gets in, Cox said, “he’s just going to shut it down.”

Fracking shale rock transformed American oil in the past decade, reversing a multi-decade decline to remake the nation as the world’s No. 1 producer and a resurgent exporter. In the process, New Mexico became the second-biggest producer in the union, second only to Texas, according to the most recent monthly data.

New Mexico wasn’t always the crown jewel of the shale patch. In fact, for much of the shale boom’s early years, it was little more than a fringe outpost tacked onto West Texas, as far as the industry was concerned. Then companies discovered the true potential of the deeper, oil-rich rock just across the state line and made their push west. Since 2017, production growth in the New Mexico Permian has been outpacing the Texas side, according to Bloomberg NEF. Federal land in Lea County now sports the lowest breakeven cost anywhere in the Permian, according to consultancy IHS Markit. Neighboring Eddy County isn’t far behind.

A key advantage is the sizeable amount of natural gas that New Mexico oil wells produce as a byproduct — as much as three times more than in the Texas Midland basin, Bloomberg NEF analyst Anastacia Dialynas said. That means companies get to capture an additional stream of revenue.

Related Story: Oil Shock Upends State That Had Become Shale’s Newest Powerhouse

“The amount of oil and gas here is crazy,” Heath Duffield, a 38-year-old superintendent at S&J Contractors, said earlier this month over the whir of a hydrovac truck that was sucking up water from a trench near a drilling site in Lea County. He counts on drilling on U.S.-owned lands for about 45% of his team’s business. Even when much of the oilfield was snuffed out by producers forced to idle rigs earlier this year, this corner of the state provided steady work.

Duffield lives in East Texas but comes to Carlsbad in Eddy County for work, staying a month at a time. Other workers moved to the area permanently, spurring a mad dash for housing. Last November, the school system surrounding Carlsbad was picking up about 300 kids daily from so-called man camps and RV parks that housed workers and their families who couldn’t snag a permanent place to live, according to John Waters, executive director of the city’s Department of Development.

Things have slowed down a bit since Covid-19 shut down much of the economy and crude prices crashed, Waters said, but not as much as he would have thought. That all changes if a new president bars oil companies from getting permits to drill on federal lands, he said.

“It scares the heck out of us,” said Jim Mayes, a foreman wearing a black sweatshirt with an American flag and a pumpjack on the back, who works on the S&J crew. “I figure they’re going to shut it down here before long.”

As the Permian boomed, so too has concern about emissions. The Delaware sub-basin, which makes up the majority of the New Mexico side of the Permian, released enough methane into the atmosphere to meet the heating and cooking needs of every home in Houston and Dallas, a group led by the Environmental Defense Fund said in an April report. Flaring, the practice by which drillers burn off excess gas, has also soared. That’s sparked criticism from environmentalists and New Mexico residents who last year urged the state to impose stricter rules governing methane emissions.