Sailing through the Bosporus Strait that divides Europe from Asia last year, a Turkish fleet saluted the tomb of 16th century pirate and admiral Barbarossa, reviving a tradition that harks back to when the Ottoman Empire ruled the Mediterranean Sea. Little noticed abroad, the tribute by sailors returning from the country’s largest-ever naval exercise now appears freighted with symbolism. As Turkey rebuilds its maritime might and contests disputed waters, it is once more in conflict with historic adversaries to the West.

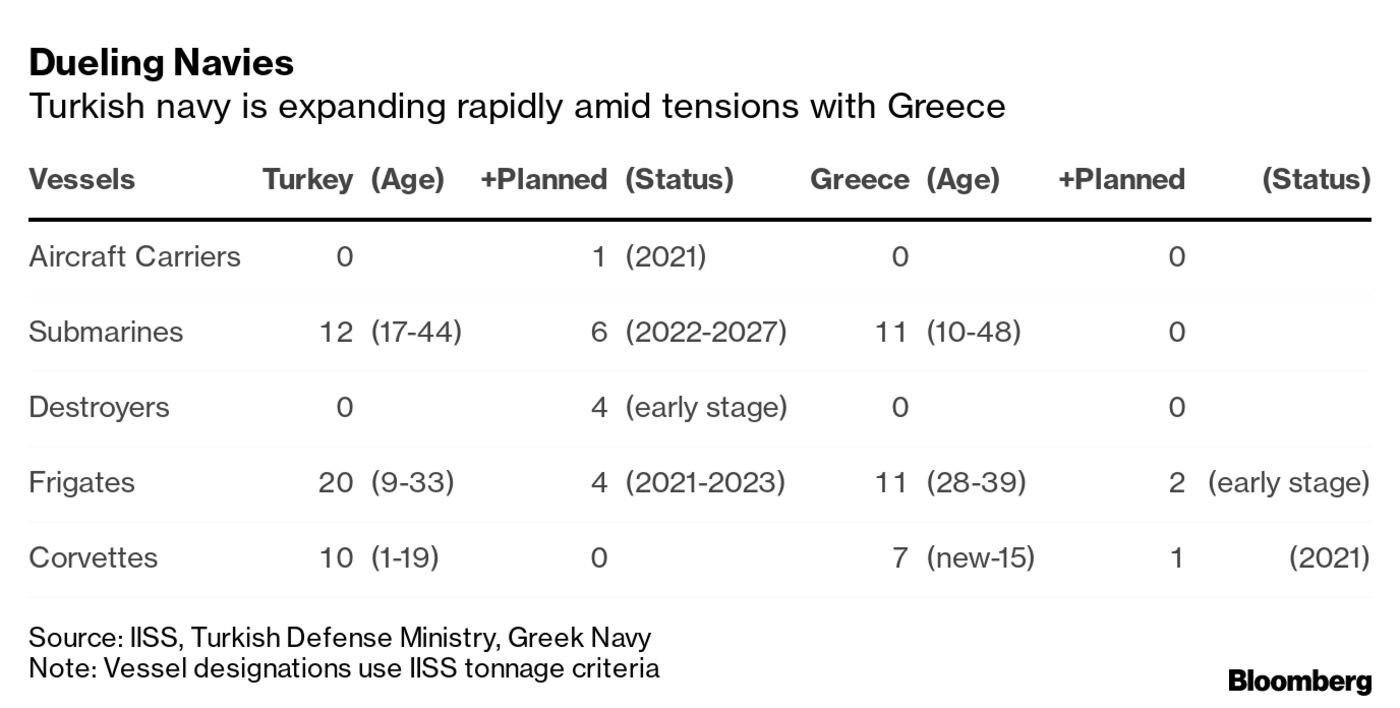

Augmented by new domestically produced surface ships and submarines, the navy has already helped Erdogan to project force abroad with a success that has surprised and alarmed other littoral states. Larger frigates are in the pipeline, and a 27,000 ton light aircraft carrier is due by next year.

QuicktakeMapping the Turkish Military’s Expanding Footprint

The boom around Turkey’s naval shipyards is part of a wider expansion of the domestic arms industry—from warships, to attack helicopters, to armed drones—aimed at gaining what Turkish officials call “strategic independence” from Western suppliers, now seen more as rivals than partners.

Erdogan has set a target of 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Republic, for Turkey to provide all of its own weaponry. That’s unlikely to be met. There are also reasons to doubt whether a troubled $750 billion economy can sustain his great power ambitions in the current climate. The European Union is also threatening sanctions over Turkey’s activities in the region.

Still, Turkey’s military has forced its way into northern Syria, ensuring a seat at the table in developments there. In Libya, Turkish warships helped supply and support the besieged government in Tripoli, turning the tide of civil war in its favor.