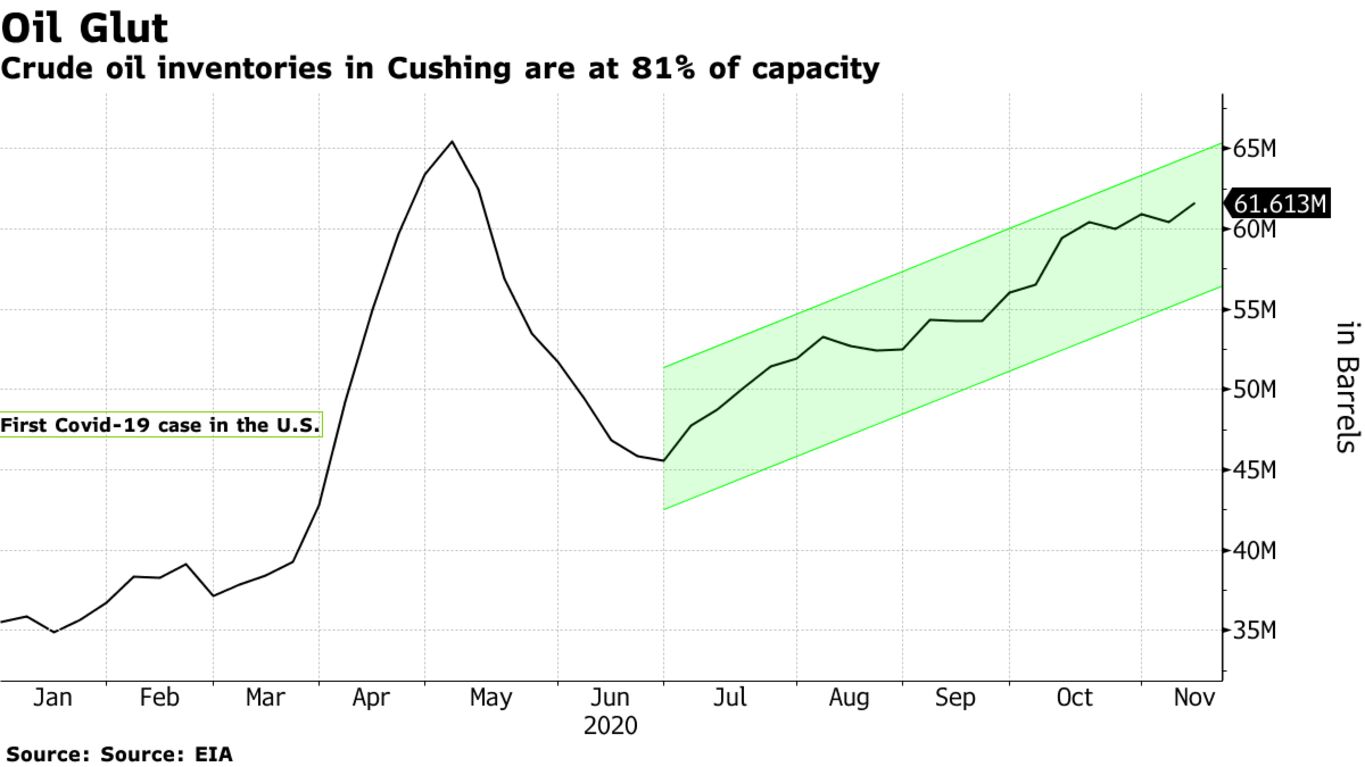

Oil tanks in America’s most important crude storage hub are filling to the brim once again, quickly approaching the critical levels reached in May after prices crashed. Stockpiles at Cushing, Oklahoma, the delivery point for West Texas Intermediate futures, stood at 61.6 million barrels as of Nov. 13, or about 81% of capacity, according to the most recent U.S. government data. That’s 3.83 million barrels shy of the levels seen in May.

Though a repeat of the negative oil prices seen in April is unlikely, the mounting supply glut brings home how lockdown measures to contain the Covid-19 pandemic may soon force traders to store oil in every nook and cranny available, including ships and pipelines. Some are already doing that.

The reasons behind the buildup are similar to what happened before: Refineries are still coping with lackluster demand as coronavirus cases surge anew. On top of that, some of them have also been undergoing seasonal maintenance. “Even as those facilities come back online, we are seeing excess inflows into Cushing overshadowing increased demand,” said Hillary Stevenson, a research director at Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

The structure of oil’s so-called futures curve has also motivated traders to store barrels. WTI has been in contango, when nearer-dated contracts are at a discount to later-dated ones. That means that, if the gap is wide enough, traders can make a profit by storing crude to sell it at a higher price later, when the glut eases.

Bets on an eventual vaccine have provided a buffer, though. And a lot has changed since the historic crash of April 20, when WTI collapsed to settle at minus $37.63 a barrel. In the months following WTI’s plunge below zero, changes swept through the oil market in the hopes of avoiding a repeat. Many clearinghouses took it upon themselves to limit how much exchange-traded funds and passive oil funds can accumulate in the nearest contract. Models have also been adjusted to account for negative prices that, up until April, were unprecedented.