It’s shaping up to be another warm winter, which could be bad news for natural gas prices. A collection of long-range government and commercial forecasts all point to the southern and eastern U.S. being warmer than normal through December, January, and February. Northern Europe will likely have milder temperatures too.

“This is all about climate change, pure and simple,” said Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. “Rising concentrations of greenhouse gases are trapping ever more heat in the lower atmosphere.”

This will have consequences for the natural gas market, a fossil fuel that’s contributing to global warming. Another mild season will knock out supports for higher prices if demand falls along with the prospect of a deep winter chill. Few winters in recent years have really provided a strong demand to push prices high.

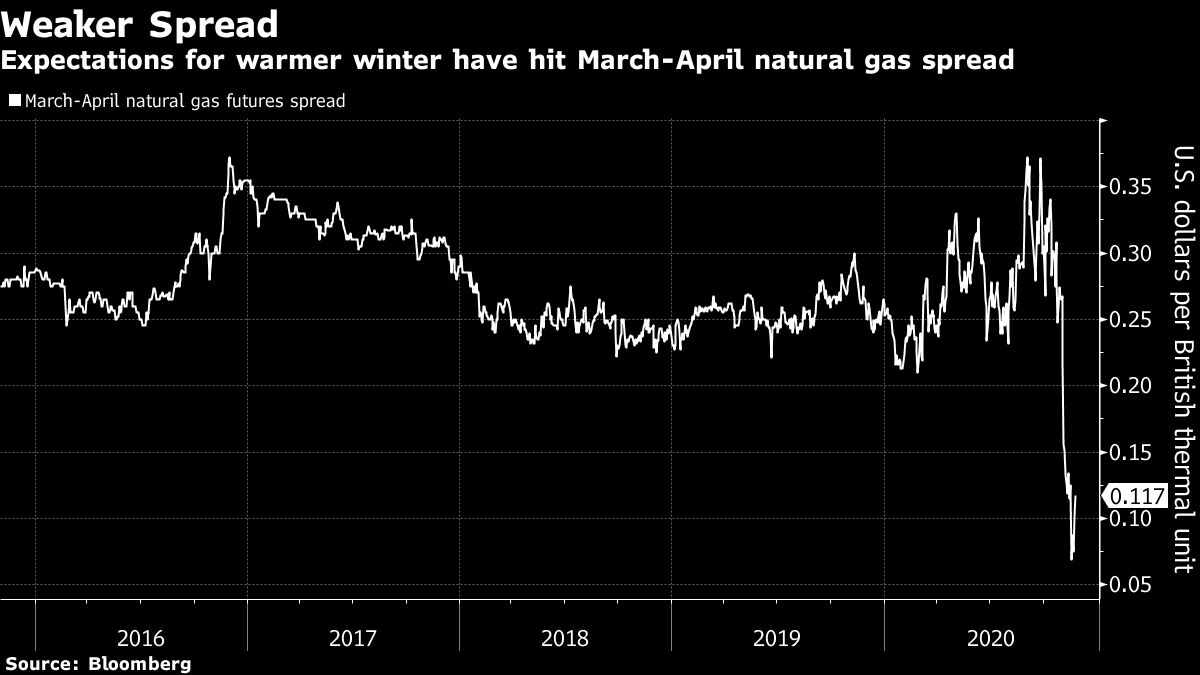

Natural gas contracts for March and April are already indicating the market is expecting a bearish winter, said Stephen Schork, president of the Schork Group. Futures prices have already plunged more than 20% in November as investors unwind bullish bets.

During a normal winter, gas futures prices would probably rise about $2 per million British thermal unit from current levels, said Phil Flynn, senior market analyst at Price Futures Group.“If we go to a warmer than normal winter, then we’re probably gonna languish with the trading rage we’re now,” he said.

This winter will be the 13th warmest for energy demand going back to 1950, according to Maxar, a commercial forecaster. December, when the heart of the heating season begins, has been showing signs of losing its strength. The number of heating-degree days — a measure of the demand for energy needed to heat a building — has declined over the last 10 years, said Matt Rogers, president of the Commodity Weather Group.

About the only parts of the contiguous 48 states that have a good chance at getting cold are parts of the Pacific Northwest and a bit of the northern Great Plains.

One difference from last year is the mounting La Nina, a cooling of the equatorial Pacific Ocean that sets off a chain reaction in global weather patterns. For the U.S., this means a warm, dry patch from California to Florida that will likely reach up the East Coast. While the La Nina winter tends to be milder, the pattern matches the long-term warming trend that has become more pronounced due to climate change, said Dan Collins, a Climate Prediction Center meteorologists, said on a conference call with reporters Thursday.

December, January, and March have all been “noticeably warmer” through the last 10 years when compared to the 30-year average, said Todd Crawford, senior meteorologist at IBM’s The Weather Company.

Meanwhile, at the North Pole a situation is developing that mirrors last year. The polar vortex, a girdle of winds that swirl around the borders of the Arctic, is starting the build. The stronger the vortex, the more the cold remains stuck over the pole, rather than spilling into the population centers of Asia, Europe, and North America.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be breaks that could spill south, but it’s unlikely. An indicator that cold might be coming is if there is a sudden, stratospheric warming over the North Pole. This is usually a sign the polar vortex is going to weaken, but it isn’t something easily forecast.

“Barring something like that I expect all of December to be mild,” said Judah Cohen, Director of Seasonal Forecasting at AER, a Verisk business. “I don’t see any sustained winter weather for a while.”