Germany is looking at using ammonia and methanol as ways to deliver hydrogen as a clean-burning fuel for industry, part of its effort to make Europe’s biggest economy climate-neutral by 2050. The government is financing a feasibility study to evaluate ways of transporting hydrogen and is focusing on the two chemicals as a possible solution, according to Stefan Kaufmann, a member of Germany’s parliament who is responsible for coordinating the use of green hydrogen in Germany.

“Options for safe and economic transport are crucial in order to establish a global hydrogen economy,” said Kaufmann in a phone interview. “We have the advantage that we can draw on an existing global infrastructure that has been in use for decades.”

Using hydrogen brings its own challenges. Transporting large amounts of the lightest element is difficult because its density is so low that it needs containers with huge volumes or to be condensed to be moved efficiently. That means storing it under high pressure or at temperatures of minus 253 degrees Celsius.

Ammonia — a common chemical comprised of one nitrogen atom surrounded by three hydrogen — is another option. Hydrogen can be converted into ammonia liquid and back again for transport around the globe. Kaufmann said Germany is looking at supply deals from Chile to Canada and Australia and that Germany will need to import 80% of its hydrogen needs if the industry takes off.

Global Game

Countries around the world are making plans to turn climate-friendly hydrogen into big business

Source: World Energy Council Germany

Hydrogen Carriers

Ammonia, which itself contains 17.6% hydrogen by weight, is the cheapest way to move hydrogen by ship, according to BloombergNEF. Currently made at fossil-fuel powered chemical plants, the compound is a key component in fertilizers for agriculture, so its shipping is well established.

One commercial hurdle is the cost of making hydrogen into ammonia and then converting it back again. It’s also toxic.

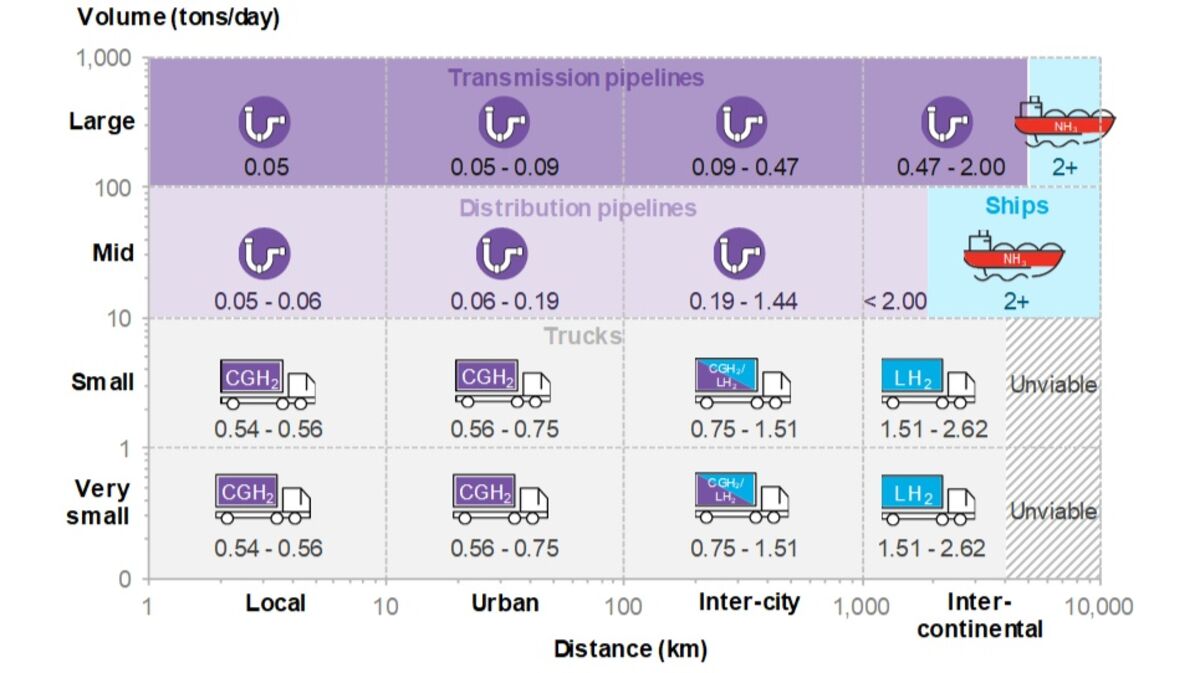

Hydrogen transport costs in the future best case, 2050 ($/Kg):

Source: BloombergNEF

“We have the experience and the equipment for bulk transport and handling these materials,” he said. “Furthermore, we can integrate them directly into pre-existing industrial processes to some extent.”

Besides transporting hydrogen by ships, Germany also plans to expand its pipelines network to reach countries offering cheap hydrogen from green sources like solar panels and wind farms.

“We envisage a European hydrogen network as a vital component in an interlinked European supergrid for energy that stretches from the Atlantic to the Baltics and from the North Cape to Gibraltar,” he said. “In the long term, we also need to integrate neighboring regions. Even if we rely on more than one transport medium, the amounts to be transported around the globe will be enormous.”