The first operators of miniature nuclear reactors described their job as “tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon” because of the danger involved with unlocking the energy in atoms Those units built more than a half century ago in the U.S. and Europe generated bursts of heat within fractions of a second so that scientists could gauge nuclear reactions, sometimes with deadly consequences. Bearing names like Godiva, Viper and Super Kukla, the reactors never fed electricity grids. Instead, they produced research useful to nuclear weapons programs and eventually utilities. Modern reactors are gigantic by comparison, able to power more than 1.5 million homes each.

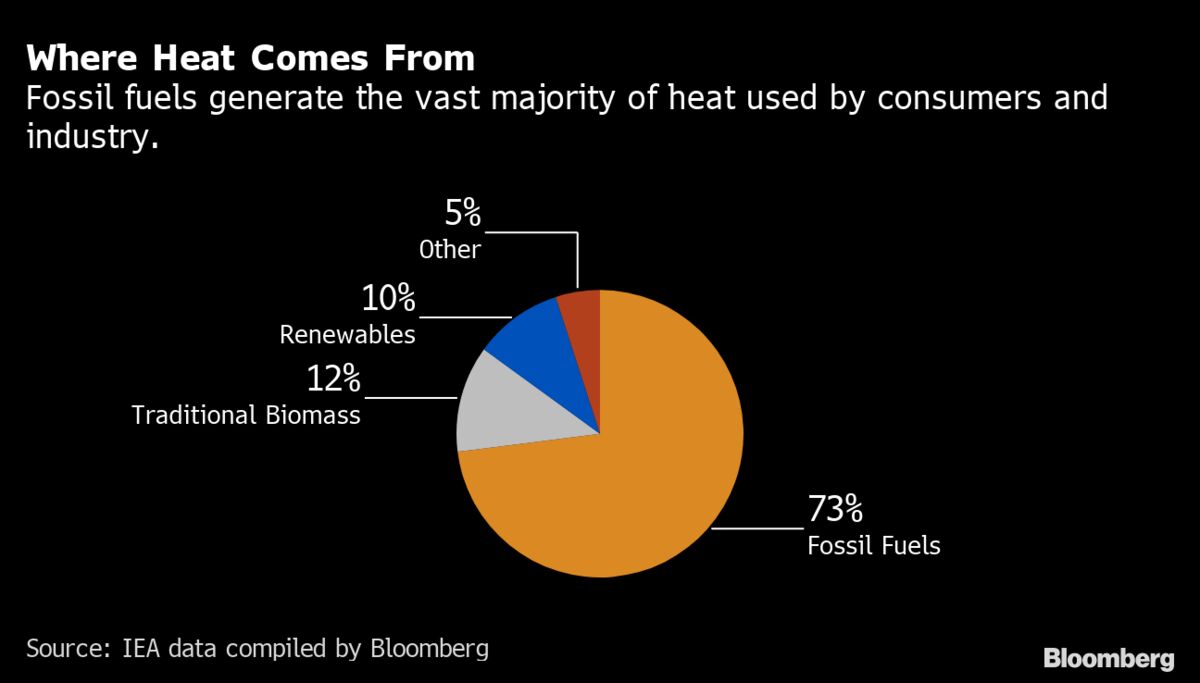

Today, the nuclear industry once again is thinking small, spurred on by politicians including U.S. President-elect Joe Biden and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson. They’re looking to solve the next climate change challenge: how to feed pollution-free heat to industries that make steel, cement, glass and chemicals. Half of the world’s energy goes into making heat, and that produces two-fifths of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, according to the International Energy Agency. Those industries sometimes need temperatures above 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,800 Fahrenheit) and more often than not burn fossil fuels to get there.

“They just need heat,” said Steve Threlfall, an executive at the nuclear fuel maker Urenco Ltd. He figures there’s a 52 billion pound ($70 billion) industrial market in the U.K. alone for reactors that can generate temperatures high enough to make ceramics, petrochemicals and steel. “It’s a particular niche market, but a very large niche.”

Small modular reactors are drawing the attention of policy makers across the U.S. and Europe because of their versatility. They can deliver a steady flow of energy both in the form of heat and electricity. The power helps balance intermittent supplies coming from wind and solar farms. The heat can help decarbonize some of the world’s dirtiest industries. Johnson set aside 500 million pounds for SMR design in a green economy program last month, and Biden says they’re one of the keys to long-term energy policy in the U.S.

Some of the biggest investors and industrial companies have gotten behind the technology, with reactor designs emerging from Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc, Fluor Corp.-backed NuScale Power LLC, Terrestrial Energy USA Inc. and TerraPower, which has drawn investment from Bill Gates. In all, there are currently 67 unique SMR technologies in various stages of development worldwide, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. That’s about a third more than just two years ago.

“This is the decade of SMR demonstrations, which could potentially determine front runners for the expected economy of series production,” said Henri Paillere, the head planning and economic studies at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. “There is high level of innovation.”

For now, only a single SMR unit is in commercial operation, installed on a barge off Russia’s Arctic coast. NuScale expects approval for one of its designs as early as next month. While the technology is advancing quickly, the economics of SMRs remain unproven. The challenge is earning enough money from a small plant to pay for the regulatory burden that comes with any nuclear venture.