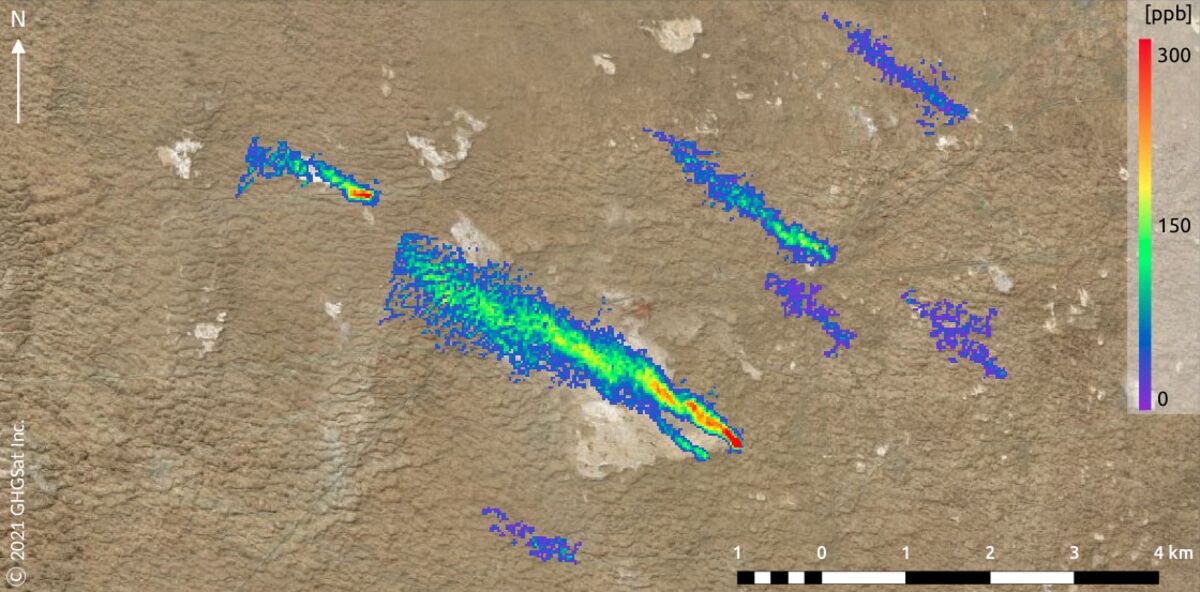

Methane leaks from at least eight natural gas pipelines and unlit flares in central Turkmenistan earlier this month released as much as 10,000 kilograms per hour of the supercharged greenhouse gas, according to imagery produced by a new satellite capable of detecting emissions from individual sites.

That amount of methane would have the planet-warming impact of driving 250,000 internal-combustion cars running for a similar amount of time, said Stephane Germain, president of GHGSat Inc., the company that picked up on the leak. The company first spotted the eight plumes of greenhouse gas on February 1. “It’s reasonable to say this happened for several hours,” he said in an interview.

This latest major leak isn’t the first time it’s found emissions originating in Turkmenistan. Last year, the company was taking satellite measurements from a volcano in the western part of the country when it accidentally revealed enormous qualities of methane rising from the nearby Korpezhe oil and gas field.

Part of GHGSat’s mission is to work with refinery and pipeline operators to stop methane leaks sooner to minimize the damage. Its ability to communicate with Turkmenistan is limited, said Germain, and time is of the essence for stopping large leaks. The satellite company has been relying on diplomatic channels through the Canadian government to try to reach the operator, but with no success so far. GHGSat declined to disclose precise coordinates for the leaks, which came from the Galkynysh Gas Field, in order to give the Turkmenistan government space to address the situation.

While this wasn’t the biggest leak GHGSat has detected, it was the first time it had captured eight separate plumes in a single image. Four of the larger plumes toward the left of the image are emissions from pipelines, he said, likely caused by problems with valves meant to control or halt fuel flows. The remaining emissions came from flares that are meant to burn fuel that can’t be transported or processed, converting it into less-potent carbon dioxide.

For now, leaks must be at least 75 feet (25 meters) apart to show up as distinct plumes in satellite imagery. But the technology is improving rapidly, making it possible to locate previously undetectable leaks, quantify their impact on global warming, and most importantly, assign responsibility. Two of GHGSat’s three satellites can detect methane leaking at a rate of 100 kilograms per hour in 50-square mile images, and the company plans to launch nine more through 2022. The European Space Agency, which has the advantage of looking over much larger swaths of land, detects leaks that release at least 10,000 kilograms per hour.

Competitors are joining the emerging field of leak detection at an accelerating rate. Bluefield Technologies Inc., for instance, was the first to identify a massive plume just north of Gainesville, Florida, in July 2020, using publicly available data captured by the ESA. A Bloomberg News report subsequently identified the likely source, a gas compressor station owned by Florida Gas Transmission, which prompted a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency investigation into a possible violation of the Clean Air Act.