Europe is so short of natural gas that the continent — usually seen as the poster child for the global fight against emissions — is turning to coal to meet electricity demand that is now back to pre-pandemic levels. Coal usage in the continent jumped 10% to 15% this year after a colder- and longer-than-usual winter left gas storage sites depleted, said Andy Sommer, team leader of fundamental analysis and modeling at Swiss trader Axpo Solutions AG. As economies reopen and people go back to the office, countries like Germany, the Netherlands and Poland turned to coal to keep the lights on.

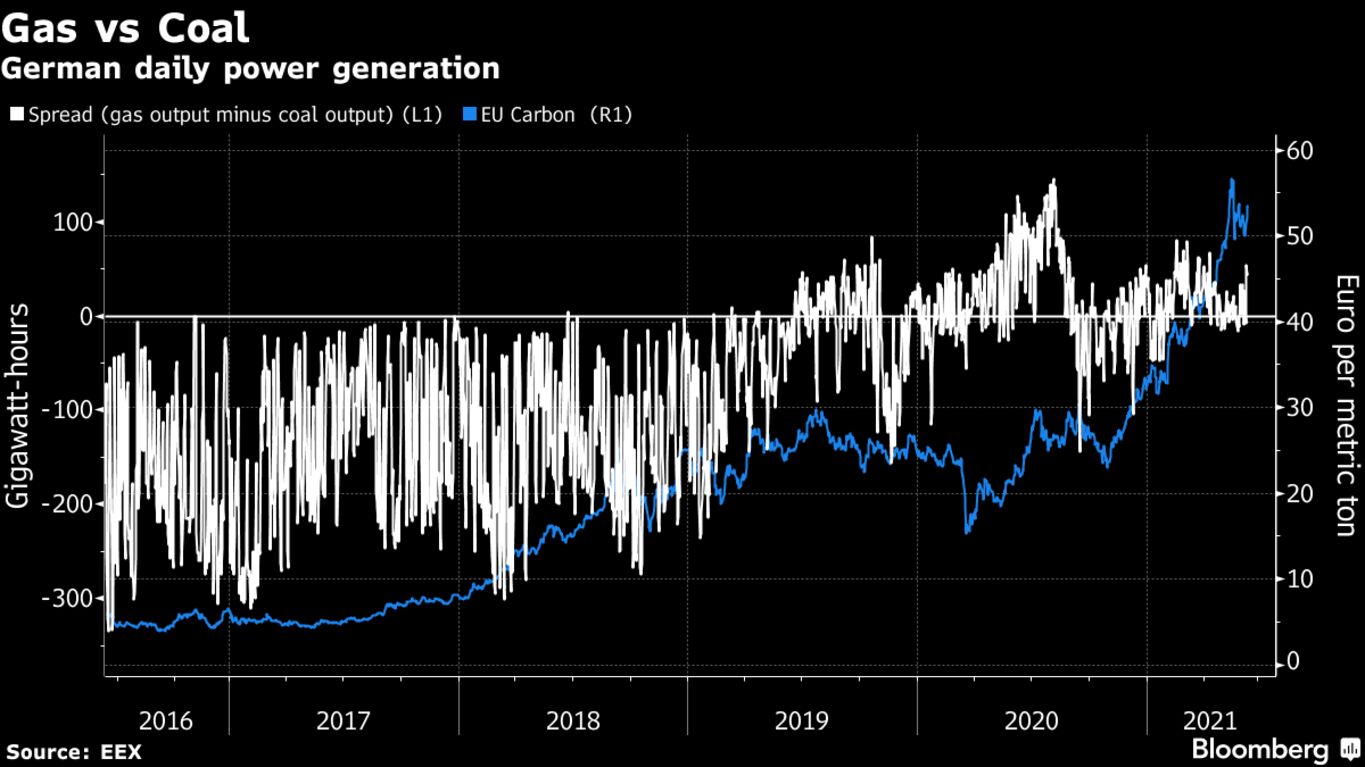

Europe has long been at the forefront of the battle to reduce global warming. The continent has the world’s largest carbon market, charging the likes of utilities, steel producers and cement makers for polluting the environment. But even with record carbon prices this year, low gas reserves mean burning coal — the dirties of fossil fuels — has become more widespread again.

“Energy demand has been pretty strong in Europe and we have seen a recovery from the pandemic,” Sommer said in an interview. “Gas storage is so low now that Europe cannot afford to run extra power generation with the fuel.”

Europe faced freezing temperatures earlier this year, boosting demand for heating at a time liquefied natural gas cargoes were being sent to Asia instead. Russia sent less gas to the continent via Ukraine ahead of the start of the Nord Stream 2 link to Germany, expected later this year.

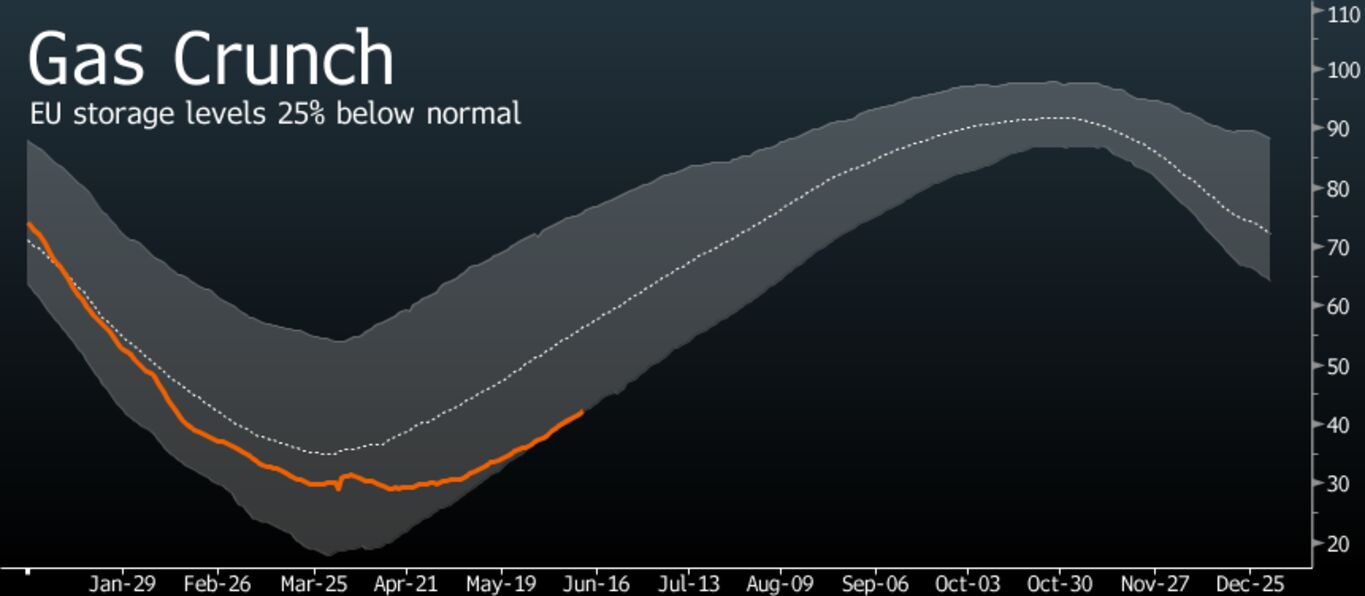

All of that mean that European storage is currently 25% below the five-year average and benchmark Dutch gas surged more than 50% this year. Futures are currently trading near their highest level for this time of the year since 2008.

“People thought Russia was going to book more capacity via Ukraine and that just hasn’t happened in a meaningful way,” said Trevor Sikorski, head of natural gas and energy transition at consultants Energy Aspects in London. “The market is super tight, it’s trying to get less gas into power.”

GIE European gas storage: percentage of full

Electricity demand, which crashed as the coronavirus locked down cities from Frankfurt to London, is now back. Usage in countries including Germany, Spain and the Czech Republic are above the five-year average, while demand is flat in Italy and France, Morgan Stanley said in a report Monday. With gas supplies already tight amid heavy maintenance cutting flows from Norway, utilities have turned to coal to keep the lights on. While the price of carbon is trading near a record, many have hedged it years in advance. That means burning coal could still be profitable.

Generators with “highly efficient” new plants can probably manage to produce power from coal until 2023, even with high carbon prices, Axpo’s Sommer said. The G-7 recognized that coal is the single biggest cause of greenhouse gas emissions in its final communique. But the group promised only to “rapidly scale-up technologies and policies that further accelerate the transition away from unabated coal capacity.”

“It’s not a great a message to be sending,” said Ursula Tonkin, portfolio manager of the Whitehelm Capital Low Carbon Core Infrastructure Fund, the Australia-based company that has $4.4 billion of assets under management in all of its funds.

While it would be “fantastic” if politicians came to a deal, coal is likely to be phased out anyway by 2030, 2035, said Tonkin. “Politics are important, but you also have the economics of the transition really kicking in within that timeframe,” she said.