We will eventually stop burning fossil fuels. The question isn’t if oil and gas fades from the picture, but whether it can happen quickly enough to stave off environmental catastrophe. Here in Louisiana, with our enormous investment in oil pipelines and tank farms fed from oil platforms in the Gulf, this is an issue of more than passing concern. It’s time now to begin thinking about how we can repurpose these potentially enormous assets.

Last month, the UN issued its dire report on climate change—Secretary General António Guterres declared the crisis a “code red for humanity.” As if to underscore the urgency of that message, Western towns and forests were consumed in drought and raging wildfires, while in the Southeast and then the Northeast, Hurricane Ida swamped the Middle Atlantic with unprecedented rainfall and flash floods.

We’re living in a world of water imbalances, but it’s one that could be righted by reusing existing infrastructure in radical new ways. This is not magical thinking. The shift to renewables is now underway worldwide. The cost of solar and wind power continues to drop, as investors pull out of oil and gas. (Even Norway’s trillion-dollar wealth fund, created from the proceeds of oil exploration and extraction, recently sold the last of its investments in fossil fuels.) The squeeze on the industry—from governments mandating electric cars to a possible carbon tax—will continue. At some point even Big Oil will succumb to the laws of economic gravity (or find new business models).

All of this will have immense consequences for our economy and the built environment. While we don’t need to shed any tears for the corporate brass and private investors enriched by fossil fuel in its heyday, the industry employs an estimated 150,000 workers and contributes nearly 8% to the U.S. GDP (a tiny percentage, we’d argue, given its immense hidden costs). The eventual demise of the oil and gas industry will also leave a vast array of idle refineries, tank farms, and abandoned off-shore drilling platforms (there are about 1,900 operating in the Gulf of Mexico alone). We believe a huge part of this vast system, the continent-spanning distribution system, holds immense promise for our warming and water-starved future, especially for drought-stricken states in the West.

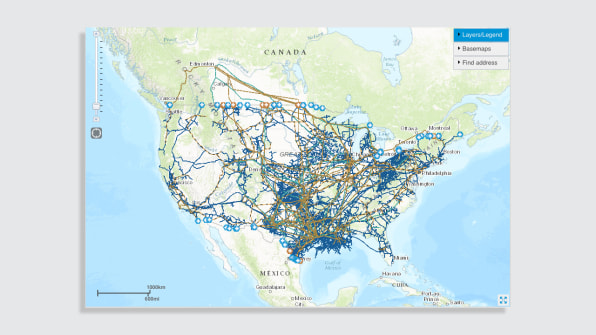

We know that extreme weather conditions will escalate in the coming years. Severe drought across the Southwest and Western regions of the United States is likely to persist and intensify. But a solution lies just underground, not in the parched aquifers, but in the pipes that have for decades channeled the fossil fuels now certifiably complicit in driving us to the brink. A staggering 2.3 million miles of oil and gas pipelines crisscross the United States, most of them with paths that end or originate in two states, Texas and Louisiana.

We are a current and a former resident of Louisiana, an oil-dependent state that has been beholden to fossil fuel companies for a century and paid a steep price for it. The Pelican State is famously rich in other ways: music, food, culture, wildlife. But our greatest resource in the foreseeable future may be our access to fresh water. In fact we spend hundreds of millions of dollars a year keeping excess water (some of it potentially potable) from inundating us. Given the water shortages in the rest of the country, this seems like a very broken paradigm.