President Joe Biden didn’t mince words as he blamed the oil industry for gasoline prices running at a seven-year high.

“Gas supply companies are paying less and making a lot more,” he said in televised remarks from the White House last week. “That’s unacceptable.

Within minutes, the oil industry and its congressional backers pointed fingers right back at the Biden administration, blaming it for policies to reduce the nation’s reliance on fossil fuels and the president’s decision to block construction of an oil pipeline from Canada.

The reality of who’s to blame for high prices — and what could be done to lower them — is more complicated. Here’s a closer look:.

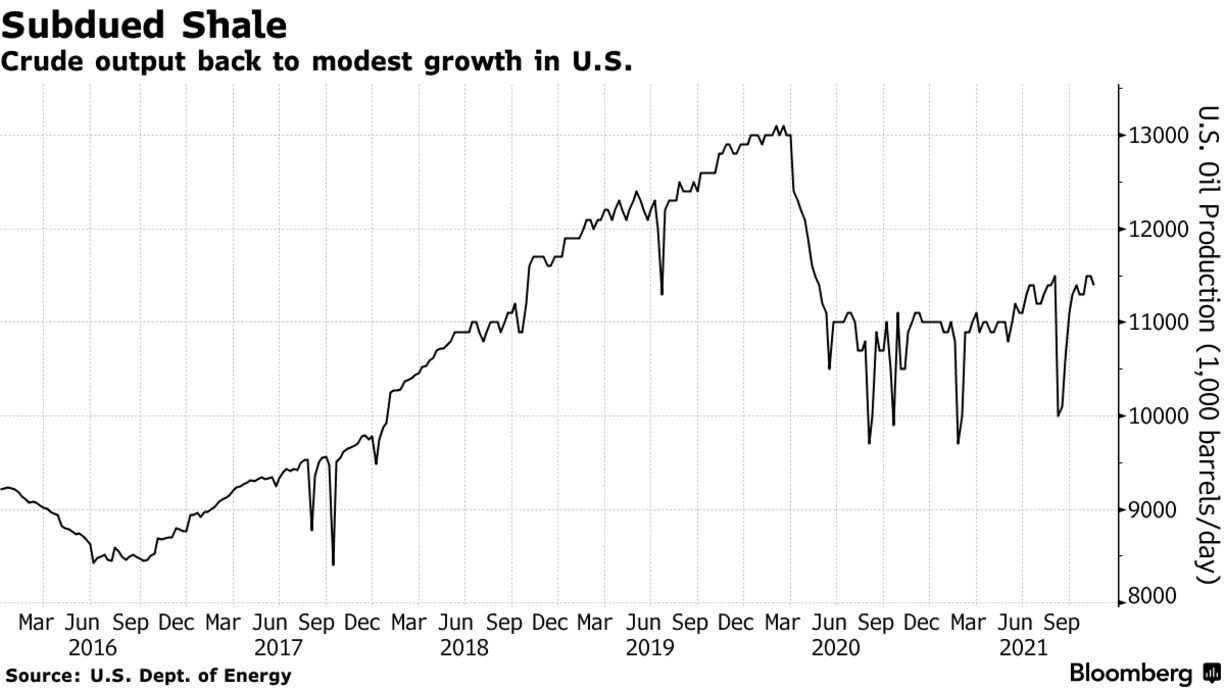

The U.S. oil industry is still producing less crude than it did before the pandemic curtailed travel and cratered demand for fuel. Even as demand returns, oil companies are keeping production flat while using profits to reward shareholders.

“Oil production is lagging behind as the economy roars back to life after the shutdown,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said recently during a White House briefing.

This year, explorers boosted output 4.5% and are expected to keep up the same pace next year. Total U.S. oil production remains 12% below pre-pandemic highs of 13.1 million barrels a day, with no sign of surpassing that in the next couple of years.

That follows a blistering four-year run that saw U.S. oil producers boost output by more than 50% between 2016 and 2020. Investors are now demanding greater returns so oil companies are forgoing crude expansion and instead returning cash to shareholders while vowing to keep spending in check.

Claim: Companies aren’t drilling all the federal tracts they’ve leased

Yes, but energy companies have a long history of renting federal land and waters with the intention to drill when the price is right.

Granholm has challenged them to take advantage of the leases they hold, noting in January that some 23 million acres of offshore and onshore tracts were leased but not producing.

But the roughly 48% of leased onshore acreage that was actually churning out crude or gas as of Sept. 30, 2020 — the most recent data available, cited by Granholm — represents a nearly two-decade high. It’s not unusual for federal leases to remain idle. Sometimes the tracts don’t contain enough crude to justify the investment and sometimes they are snapped up by speculators on the cheap.

“Companies are buying an option — not an obligation” to use the leases, said Kevin Book, managing director of research firm ClearView Energy Partners. “It’s not market manipulative behavior, it’s market-responsive behavior.”

Oil companies, which must pay rental fees to retain leases over their 10-year lifespans, make decisions about using them based on crude price forecasts and the costs of those acquisitions.

Moreover, drilling all the federal leases today would not yield crude immediately, if at all.

Idle Land

Less than half of leased federal acreage produces oil or gas

Source: U.S. Bureau of Land Management

Claim: The Keystone XL pipeline could have eased the supply crunch

Even if Biden hadn’t yanked its permit, the Keystone XL pipeline wouldn’t have been operational now. But there could have been a long-term impact and some lawmakers — including Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia — have cited it in blaming the administration.

“If you had built it a decade ago, maybe oil prices are a little cheaper, maybe fuel prices are a little cheaper,” said Benjamin Salisbury, director of research with Height Capital Markets.

Within hours of his swearing-in, Biden revoked a presidential permit for the controversial pipeline, which would have transported up to 900,000 barrels per day of Canadian crude to U.S. refineries.