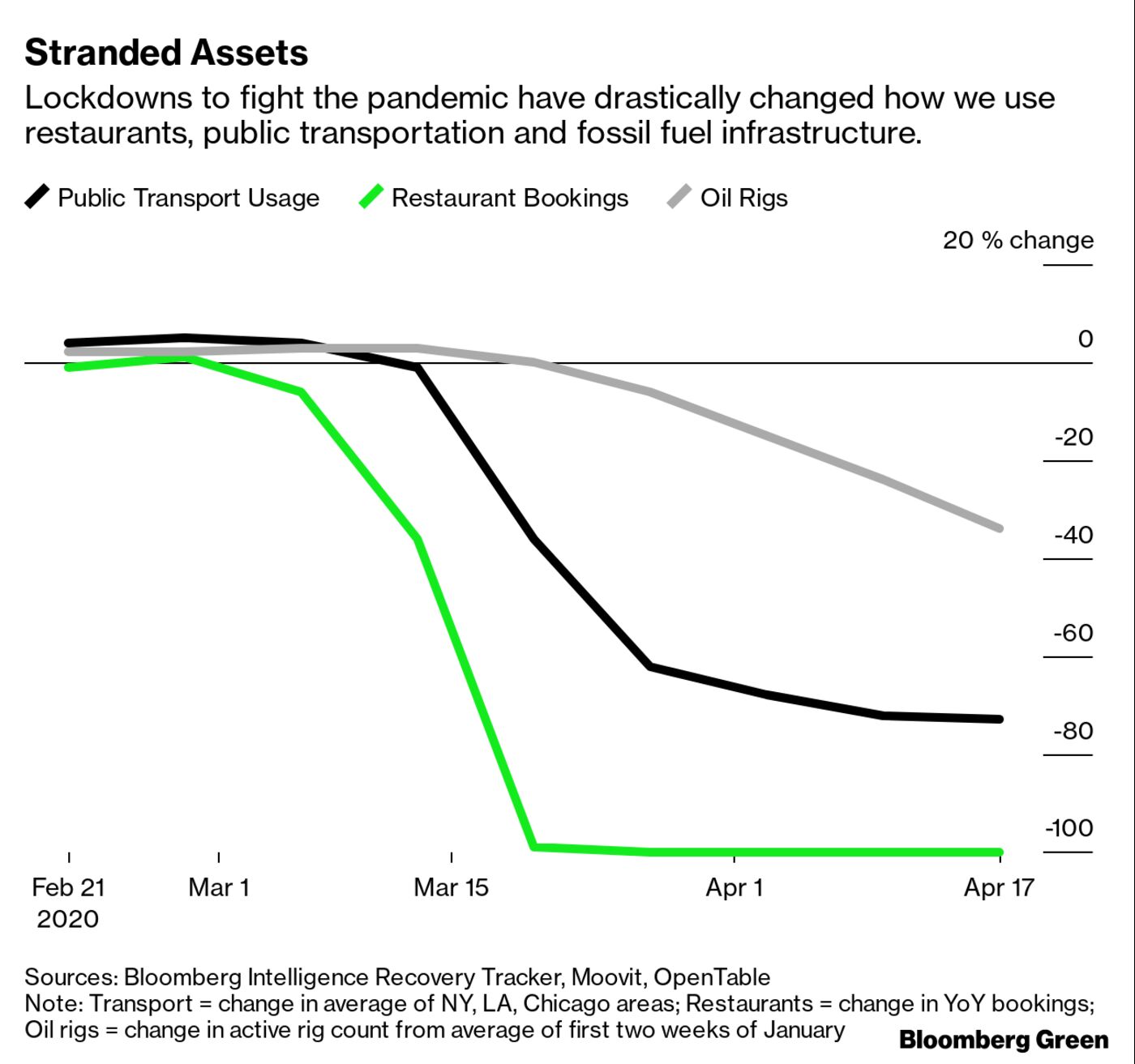

Stranded assets used to be a niche idea. The concept that fossil fuel infrastructure wouldn’t be used is one that’s been championed over the last decade by the U.K.’s Carbon Tracker think tank. These days, financial regulators have joined in. That prophecy has certainly been on display in the oil and gas sector over the past few weeks. And everywhere else. Empty restaurants. Shuttered theaters and hotels. Grounded airplanes. At least at the moment, they all fit the definition of stranded assets subject to premature writedowns and operating losses. Everyone is getting a close look at the vast economic and human costs associated with investing in infrastructure that can’t be used, even temporarily. The threat of bankruptcy and restructuring suddenly spans the global economy from offshore drilling to retail. Just as fossil fuel use will ultimately be bound by a planetary carbon budget, we’re now looking to rebuild society around the outer limits of hospital bed capacity and infection rates.

“We’ve been warning for years that overcapacity was going to come, and though nobody foresaw this, what the Covid shock has done is drag that forward and manifest the risks of low-growth sectors earlier,” said Kingsmill Bond, Carbon Tracker’s energy transition strategist. “For those industries that were already vulnerable and struggling to make it, this just pushes them over the edge.”

It’s no surprise that Wall Street is giving up on some fossil fuel asset classes that already looked bad a few months ago. Now they look much worse, since prices have collapsed and storage options for unsold stock are running thin. Morgan Stanley this week became the latest U.S. bank to rule out financing Arctic oil, joining Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan and Wells Fargo in barring future funding of these expensive projects. If prices stay where they are, high-cost oil projects will become “zombie assets” that run production without financial returns, Bond said.

Investors have just started pressuring other sectors about their stranded assets. Utilities, for example, faced several shareholder proposals seeking better disclosure on the risks (Southern Co. told investors it would provide the information). Regulators told Sempra Energy and Dominion Energy they could exclude similar proposals from their proxy ballots this year. But even without a proposal, there’s no better time for companies to talk about how they plan to rethink their current assets.