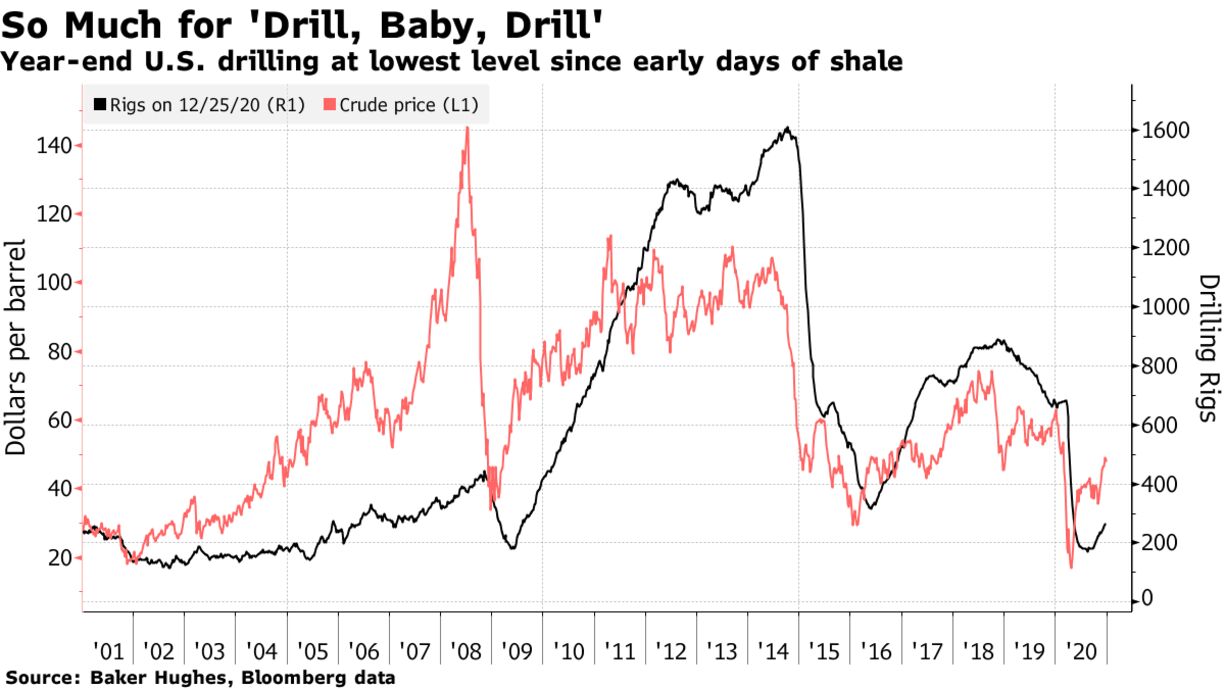

The crisis that enveloped the oil industry in 2020 can be measured in various ways, but in the U.S. there may be no better single gauge than the tally of drilling rigs operating across the world’s largest producer. The weekly data shows at a glance the level of confidence from hundreds of companies that sink shale wells from Texas to North Dakota. As the price of crude plunged amid the pandemic, those operators slashed spending and cut drilling crews.

The result was a rig count that collapsed to levels not seen since the advent of the shale era 15 years ago, as crude demand and prices plunged. And while the data has rebounded since August, it still remains far below where it began 2020. Next year isn’t expected to get much better with U.S. oil prices widely expected to be stranded between $40 and $50 a barrel, forcing explorers to make hard choices about whether new drilling is worth it.

The number of rigs drilling for oil in the U.S. closed out 2020 at 267, according to Baker Hughes Co. data released Wednesday. It’s the lowest end-of-year figure since 2005, when drilling and fracking breakthroughs perfected in natural gas regions like North Texas’s Barnett Shale were just beginning to be deployed in crude fields.

The slump reflects a huge readjustment for the U.S. oil industry. Having ridden to a position of global preeminence on the back of the shale boom, the U.S. reemerged as a major exporter rivaling Saudi Arabia and Russia, but the pandemic hit hard and forced producers to make painful cost cuts. Domestic output is ending the year steady but about 16%, or 2.1 million barrels a day, below its pre-pandemic peak, a level where it’s widely expected to stay absent a dramatic price spike. In the meantime, OPEC has managed to regain its former position as the dominant player in the global market.

On the ground in places like West Texas and North Dakota, the plunging rig count signifies a painful year for the U.S. oil services sector, which does the drilling and fracking. Dozens of companies filed for bankruptcy in 2020, and tens of thousands of jobs were lost. Industry giant Schlumberger abandoned frack work entirely in North America, a sign that activity in the U.S. shale patch may never revisit previous highs.

Shale Patch Shutdown

Timid drilling recovery in top basins still leaves rig counts way below levels of recent years

Source: Baker Hughes data through Dec. 31

Drilling activity is slowly recovering, partly because output from shale deposits declines more quickly than conventional wells. Simply maintaining production levels requires additional fracking. Still, U.S. oil executives remain wary of plowing significant sums into new exploration because of the supply glut that began weighing on prices in early 2020 and only worsened as the Covid-19 pandemic paralyzed economies around the world.

“North American E&Ps are in a battle for investment relevance, not a battle for global market share,” Matt Gallagher, chief executive officer at Parsley Energy Inc., told analysts during a conference call in August. “Allocating growth capital into a global market with artificially constrained supply is a trap our industry has fallen into time and time again.”

A week after Gallagher’s remarks, the nationwide rig tally dipped to a 15-year low of 172, and a short time later he agreed to sell Parsley to rival Pioneer Natural Resources Co. for about $5 billion in stock.

Since the August nadir, shale plays in Texas have shown the biggest rebounds. The Permian Basin in West Texas and New Mexico, North America’s most-prolific oil field, has seen 15 straight weeks of rising or steady drilling activity. The rush has been spurred in part by drillers’ concerns that President-elect Joe Biden may hinder fracking on federally-owned land in the New Mexico section of the Permian.

Meanwhile, places like the Bakken in North Dakota and the DJ-Niobrara in Colorado have been slower to recover because they are more costly — and thus, less profitable — to drill.

Spending Slump

Estimated U.S. oilfield spending in 2021 still far below 2019 levels

Source: Evercore ISI

After U.S. explorers slashed spending almost in half this year, they’re expected to raise outlays by a mere 5% in 2021, according to Evercore ISI. In other regions around the world, including Latin America and Europe, expenditures are forecast to grow more robustly, according to Evercore.

In the U.S., much of that new spending is expected to finance fracking rather than new drilling as explorers such as Callon Petroleum Co. chew into a large supply of pre-drilled wells that were never finished because of the price crash.