At first glance, big corporations appear to be protecting great swaths of U.S. forests in the fight against climate change. JPMorgan Chase & Co. has paid almost $1 million to preserve forestland in eastern Pennsylvania. Forty miles away, Walt Disney Co. has spent hundreds of thousands to keep the city of Bethlehem, Pa., from aggressively harvesting a forest that surrounds its reservoirs. Across the state line in New York, investment giant BlackRock Inc. has paid thousands to the city of Albany to refrain from cutting trees around its reservoirs.

JPMorgan, Disney, and BlackRock tout these projects as an important mechanism for slashing their own large carbon footprints. By funding the preservation of carbon-absorbing forests, the companies say, they’re offsetting the carbon-producing impact of their global operations. But in all of those cases, the land was never threatened; the trees were already part of well-preserved forests.

Rather than dramatically change their operations—JPMorgan executives continue to jet around the globe, Disney’s cruise ships still burn oil, and BlackRock’s office buildings gobble up electricity—the corporations are working with the Nature Conservancy, the world’s largest environmental group, to employ far-fetched logic to help absolve them of their climate sins. By taking credit for saving well-protected land, these companies are reducing nowhere near the pollution that they claim.

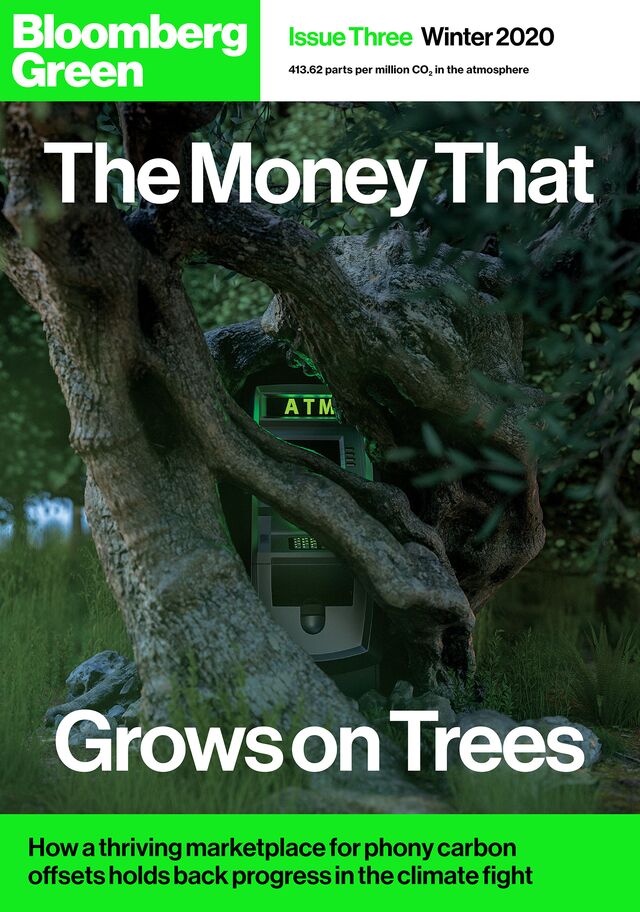

The Nature Conservancy recruits landowners and enrolls its own well-protected properties in carbon-offset projects, which generate credits that give big companies an inexpensive way to claim large emissions reductions. In these transactions, each metric ton of reduced emissions is represented by a financial instrument known as a carbon offset. The corporations buy the offsets, with the money flowing to the landowners and the Conservancy. The corporate buyers then use those credits to subtract an equivalent amount of emissions from their own ledgers.

Few have jumped into this growing market with as much zeal as the Nature Conservancy, which was founded 69 years ago by a small group of ecologists seeking to preserve the last unspoiled lands in the U.S. In the seven decades since, the nonprofit in Arlington, Va., has grown into an environmental juggernaut, protecting more than 125 million acres. Last year its revenue was $932 million, which eclipsed the combined budgets of the country’s next three largest environmental nonprofits.